Emotional stress in dogs

A close-up look at emotional stress in dogs — and how our own stress contributes to theirs.

None of us is a stranger to stress. It affects many levels of our lives, and it also affects our dogs. Generally, the human and animal body is influenced by three types of stress: chemical (pesticides, medications, vaccinations, by-products of normal metabolism), physical (injuries, exercise), and emotional (thoughts, perceptions, experiences). This first of this two-part article will focus on the emotional aspect of stress, and how our own stress affects our dogs.

What exactly is stress?

Stress is defined as state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or very demanding circumstances. It’s the emotion we feel in response to something that occurred outside of ourselves. This feeling or emotion is intimately involved with the basic biological instinct for survival. Physiologically, this is represented by the “fight or flight” mechanism, an elegant built-in biophysiological design that is instantaneous and automatic and involves a precise orchestration of events.

Although this mechanism is designed to protect us, times have changed, and nowadays many real threats have turned into perceived threats, which means most of our fears are coming from internal sources.

The anatomy of stress

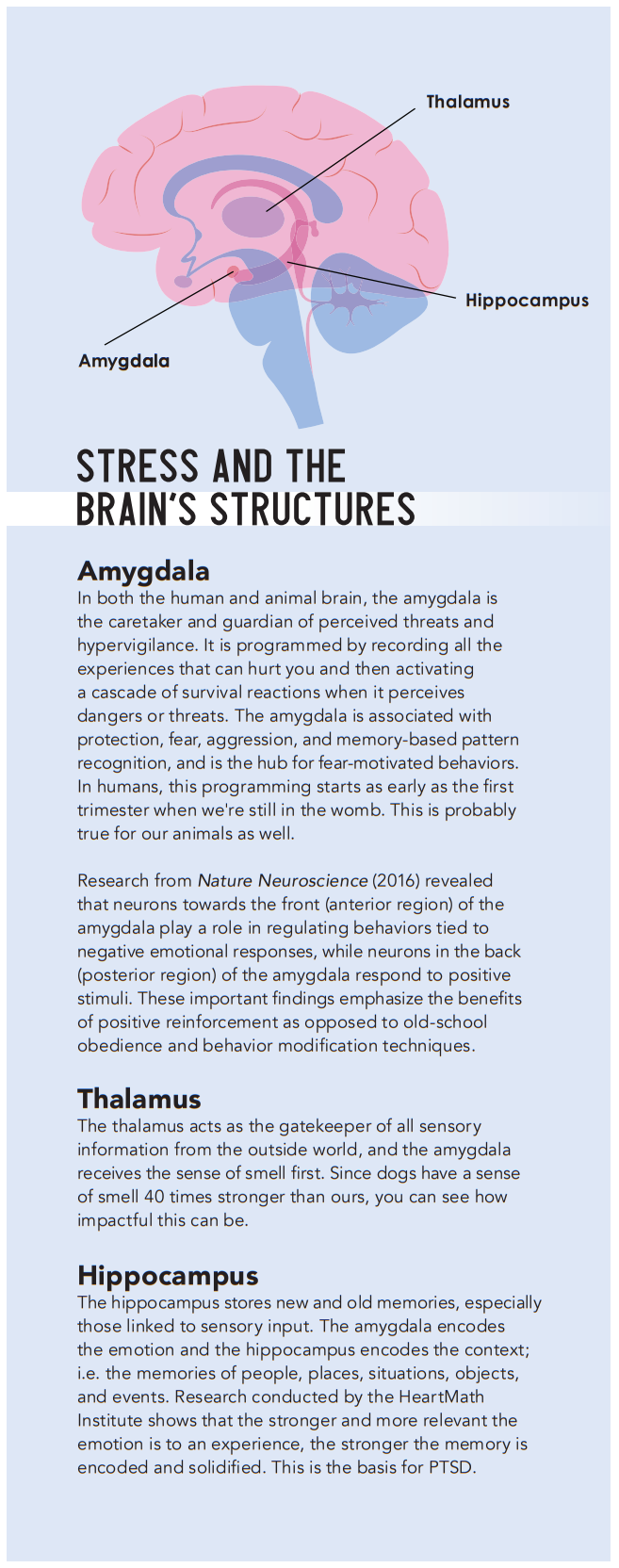

It helps to understand stress if we understand the anatomical structures that play a part in it. Because the stress response is a primitive survival mechanism, all mammals have it, including dogs and humans. Regardless of species, the structures in our bodies that regulate how we respond or react to stress are the same.

The major players in the stress response are:

- Limbic system (or emotional center) in the brain, made up of the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala (see sidebar)

- Brainstem

- Adrenal glands

- Sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system.

These systems work together to help ensure survival by dilating the pupils to let in light for better eyesight; increasing the heart rate to pump more blood to muscles used for running and fighting; increasing respiration to get more oxygen to the tissues; and inhibiting or shutting down the higher thinking areas of the brain. Moments of survival are not a time to think, ponder, plan, or rationalize – they are a time to act!

These systems work together to help ensure survival by dilating the pupils to let in light for better eyesight; increasing the heart rate to pump more blood to muscles used for running and fighting; increasing respiration to get more oxygen to the tissues; and inhibiting or shutting down the higher thinking areas of the brain. Moments of survival are not a time to think, ponder, plan, or rationalize – they are a time to act!

This reaction is highly appropriate when needed. However, the fight or flight system was designed to be short-lived. Long-term stress responses have been implicated as the underlying causes of multitudes of health conditions.

How this relates to dogs

Wild animals use this system innately to hunt, escape or fight a predator, or fight each other in a battle of dominance to establish order and breeding rights. After the “episode”, the animal goes back to resting, sleeping, feeding, or whatever he was doing before the stressful event. The body resets.

But times have changed for our dogs as well as for us. They have become an integral part of human life and the families they live with. Most dogs don’t need to hunt for food or fight for breeding rights, and they rarely need to defend themselves against predators. In other words, their food is delivered, they sleep in comfy beds, and are sheltered from impending threats.

Like us, dogs need a sense of purpose or self-worth. Subtle psychological attributes like self-worth may be debatable in canines, but if you’ve ever been in the presence of a police dog or other “working” dog, and watched him in action, you can see and feel the pride he takes in doing a good job.

When dogs are not doing what they are hard-wired to do, they will become stressed and divert their energy “sideways”, with destructive tendencies. And when we or our animals feel a lack of self-esteem, it creates uncertainties and limited beliefs, which in our dogs manifest as a fear of separation, being left alone or abandoned.

Stress has been normalized

Unfortunately, the stress mechanism has evolved from a necessary protective tool into a normalized state of everyday life. This has impacted us, our animals, and our society in profound psychological, emotional, and physical ways.

Stress is the underlying process that drives most disease. The once necessary fight or flight system called upon to protect the physical being is being habitually used by humans in the form of constant mental chatter, worries, and negative, depleting thought processes. we flee within into a state of emotional withdrawal, sadness, depression, anxiety, aggression or anger. Instead of fighting a bear or other prey animals, we lash out at others with anger, judgments, and hurtful statements. We fidget, tap our fingers, shake our legs, click our pens, twirl our hair, and develop self-defacing nervous habits. We learn to live in survival mode, and become so familiar and accustomed to it that we don’t even recognize the effects it’s having on our physiology and emotional state of being.

Stress is the underlying process that drives most disease. The once necessary fight or flight system called upon to protect the physical being is being habitually used by humans in the form of constant mental chatter, worries, and negative, depleting thought processes. we flee within into a state of emotional withdrawal, sadness, depression, anxiety, aggression or anger. Instead of fighting a bear or other prey animals, we lash out at others with anger, judgments, and hurtful statements. We fidget, tap our fingers, shake our legs, click our pens, twirl our hair, and develop self-defacing nervous habits. We learn to live in survival mode, and become so familiar and accustomed to it that we don’t even recognize the effects it’s having on our physiology and emotional state of being.

Although we may not be aware of it, our dogs are sensing and processing our stress energy, and it shows up as behavior and physiological changes. Dogs will display their stress through aggressive behaviors like growling, barking or biting, or fear behaviors such as hiding, pacing, panting, yawning, chewing (on objects or themselves), and over or under grooming. Indiscriminate or submissive urination can also be sign of stress in dogs.

The long term effects of stress

If the underlying cause of stress is not addressed and rectified, it will lead to deeper states of disease in both humans and dogs. This is when we see the physiological manifestations. There is an inverse relationship between stress hormones and the immune system. Meaning, as cortisol levels go up, the immune system weakens.

Some health conditions associated with stress are vomiting, diarrhea, heartburn, gastric reflux, loss of appetite, too much appetite, heart conditions, arrhythmias, hormonal conditions affecting the adrenal glands, allergies, asthma, increased bacterial or viral infections, accelerated aging and premature death.

In short, stress is not just a word. It is a phenomenon associated with a multitude of layers, processes and interactions between the body, the mind, the environment, and other people. Understanding it can be complex, but the solutions can be simple. The next part of this article will look at various modalities to de-stress your dog, and yourself!